Who knoweth the spirit of man that goeth upward, and the spirit of the beast that goeth downward to the earth? (Ecclesiastes 3:21)

If the Book of Revelation is not a tragic piece it is because the main character is missing. No matter how hard we attempt to convince ourselves that the protagonist is humanity (at least a selected part of it, the underdogs turned VIPs) rightfully taking center stage, the conspicuous absence of the one that is best of us is decidedly baffling, if not intolerable. He, the anointed, Jesus Christ, makes spectacular flash appearances such as the Son of Man of Revelation 1.13, or the logos on a white horse of Rev. 19.13. And yet, what is most characteristic of Jesus in the New Testament, his love for us, is totally absent from John’s account: the suffering is there, but the Jesus we know is not. If John of Patrmos had Jesus in mind, the one presented to us by the four evangelist, he may have known something that his predecessors did not want to tell us, or only did occasionally.

In that realm, the symbolic realm of light, the figure of Christ like that of every humanizing and civilizing hero projects something of a shadow: a shadow-of-light, if you will. These are images that reflect the deep recesses of the human soul, and that in that luminous place portrayed in the Book of Revelation acquire colossal proportions. The sacred history of Jesus is that of the divinity made human; a humanity that knows all good and is capable of all evil. But above all a humanity that knows of the almost magical power of the word: saying yes, and saying no, are still the most devastating weapons known to humanity, and the most feared and persecuted as well. The form of Christ in the kingdom of light, his “secret” history, is what is related in the Book of Revelation, which in that sense is a description of a Christ reunited with a divinity that appears distant to us, if not remote: the love and tenderness so characteristic of Christ hardly reaches us from there; perhaps because the human is already divine, and now we find ourselves in the presence of a vision of divinity that transcends the kind and merciful image that he showed in his short journey between Nazareth and Jerusalem. Love and tenderness are gifts from the divine, essential to negotiate the survival of the human race.

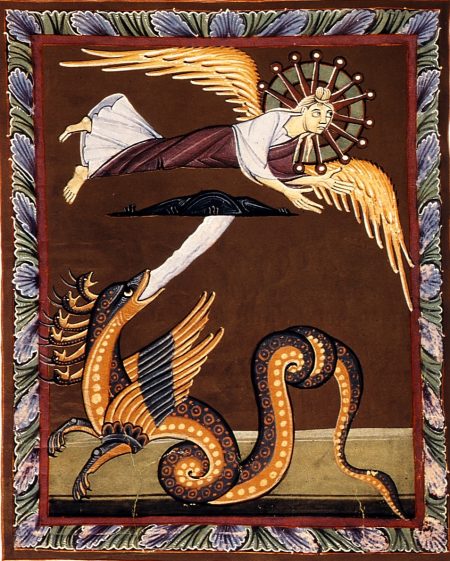

And then there is the “woman clothed with the sun”.

Why did John, of all things, inserted this episode in the middle of the work? Is there really a point to it, or was he just following some previous apocalyptic model (or, worse, quoting some pagan myth right in the middle of his very opinionated account of the last days)? John sounds often like a bigot (Rev. 2 and 3 are almost scandalous in this sense – and if you still are not convinced just see who is excluded of the heavenly light in Rev. 21 and 22, or otherwise take a closer look at Rev. 18). And yet, Revelation 12 offers the reader a glimpse of the otherworldly in a manner that is almost uncharacteristic, almost in passing, and certainly never retaken. I, for one, would have expected the connection between chapters 12 and 21-22 of the book to be more obvious: I would have expected the woman, or the son of the woman, to be mentioned clearly at the end of all things. And yet, Revelation 12 is possibly the most powerful and breathtaking chapter in the whole book.

A great sign appeared in the sky: a Woman, clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet, and a crown of

Rev. 12:1

twelve stars above her head.

Feminist criticism has had difficulties accepting John’s account of the women figures in the Book of Revelation. And I agree with that criticism to a very large extent. Women are depicted in a very (too) categorical manner as virgin/mother/whore or hag. Hopefully one day soon we will not have to refer to “feminist” whatever anymore, having assimilated what it very clearly is a universal fact: men and women are complementary and the predominance of one or the other will always be tantamount of a humanity out of balance. History, which can always be read in different ways, should not be an excuse for either revenge or worse, leaving our task unfulfilled: conciliating past facts in order to build bridges for a future understanding beyond thought-structuring, society manipulating male archetypes. John of Patmos, a hell of an enigmatic character (bordering sometime on insanity, it seems to me, and not necessarily a male chauvinist), was not there yet.

For some authors the woman in Rev. 12 is a more complex symbol. Elaine Pagels, in an interesting footnote recounts that since very early “Christians often have interpreted [the woman clothed with the sun…] as Mary, since she is characterized as mother of the messiah or else as the church. Others, likely including John himself, inspired by the image that the prophet Isaiah offers in Isaiah 26:17–27:1, apparently thought of her as the nation of Israel as potentially pregnant with the messiah […]”. The radiant woman as Mary at least has the advantage of bringing the human and the humane through the back door, so to say. Artists in particular have chosen this link to add some of the lacking colors to the Book of Revelation, such as Velázquez’s Immaculate Conception, and I quote:

If in Revelation the Lamb represents the ultimate triumph of the victim and the innocent, the Woman Clothed with the Sun is a strong affirmation from within Christianity’s most confrontational book of the power and necessity of the anima, of the female principle.

Picturing the Apocalypse, Natasha O’Hear and Anthony O’Hear, OUP 2015

Continuing with Pagels, she emphasizes that we do not need to choose one particular interpretation to the detriment of the others, since (and she mentions John J. Collins’s book The Apocalyptic Imagination: An Introduction to the Jewish Matrix of Christianity) “apocalyptic images” after all, may be characterized as “multivalent,” that is, capable of suggesting more than one meaning—often a cluster of related meanings.”

(See E. Pagels, Revelations: Visions, Prophecy, and Politics in the Book of Revelation, Ch. 1, n. 12; 2012 Viking Penguin).

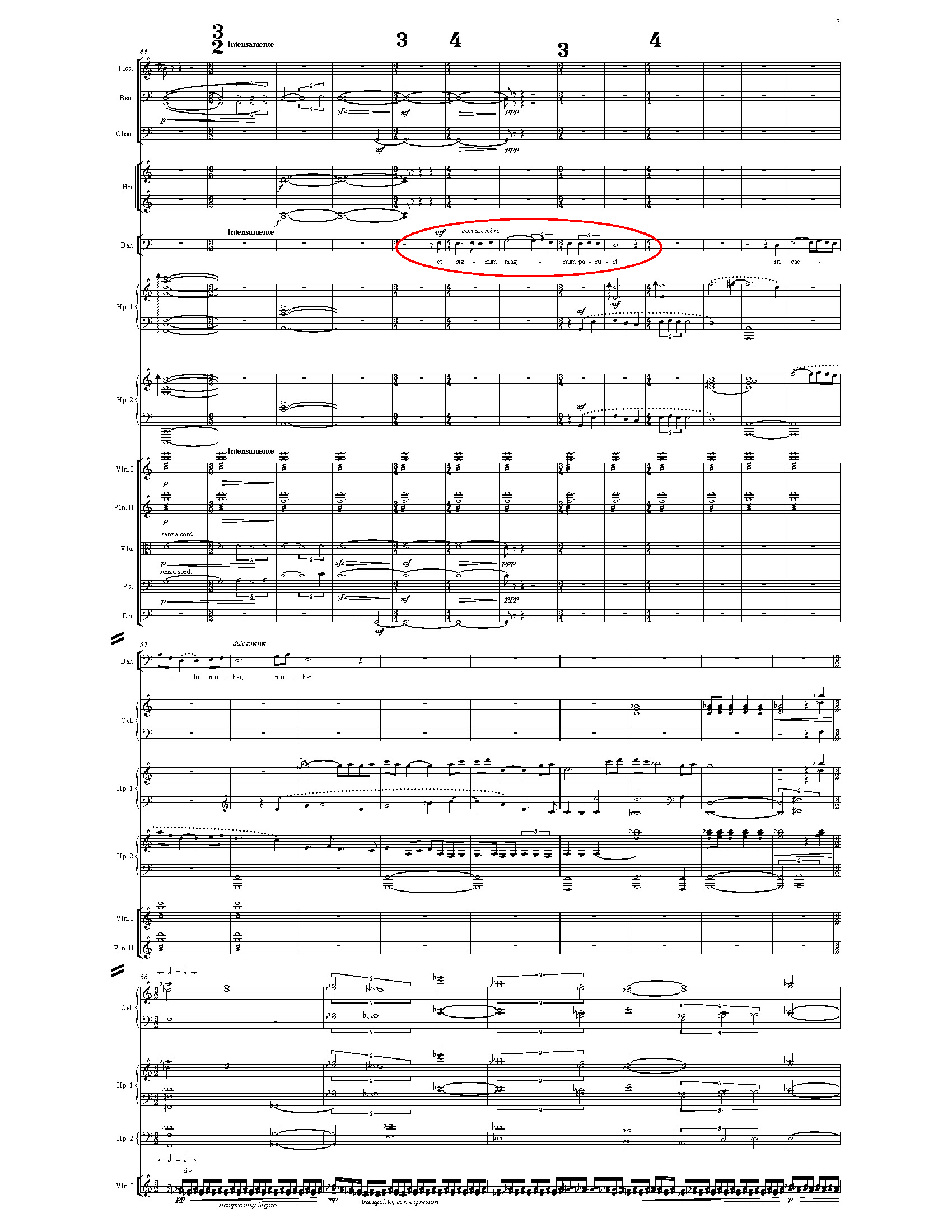

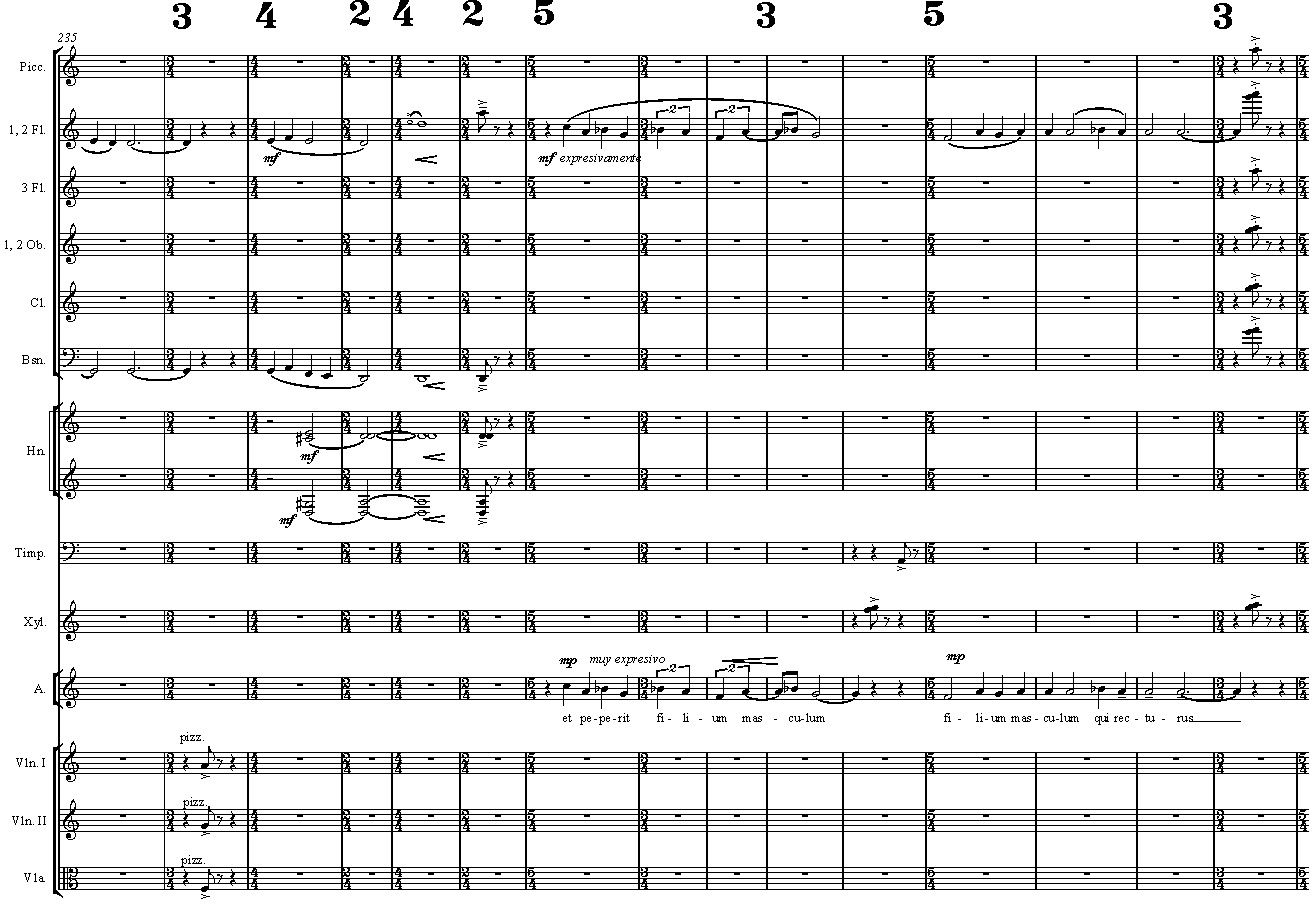

Musically speaking, a superficially descriptive or over-dramatized treatment of the Book of Revelation would tend to caricature a work that is in itself highly ironic in handling its, very much so, antiheroes. As far as the Apocalypsis Iesu is concerned, writing the score (now finished) of Revelation 12 took me a great deal of consideration: I simply did not think that I was mature enough, spiritually, to sit down and write about what is undoubtedly the most harrowing account of the book, the most profound, and the most pregnant, literally, with meaning. Not that I could say that I am now, who could really. But something changed all that, something that made me decide there and then that it was time for Revelation 12: that something was the music of I will leave the reader, or the expert, decide the particulars of this, such as which piece in particular truly opened the door in the sky for me. There is certainly more than a frivolous borrowing of Machaut’s materials, be it a thread of a melody, his haunting open harmonies, the cadencing of happiness and sadness. Much more. Machaut brought the sublime into my life at a moment where hell was all around, crawling and creeping, invading and destroying whatever was left of my inner self: he brought a continental breeze and fertilizing drizzle to my life.

(Wikipedia Commons)

The sheer beauty of this Machaut’s music, this poet, composer, gave me the courage to write a score that, in any other circumstance, would be simply a daring slur on what I considered to be the core of the work. The woman clothed with the sun may be understood as Mary, the Virgin, or a multifaceted symbol of the feminine in us and around us (why not!). But it brings the human home, and that I could not dare to trivialize. True, there is still the issue of whether the narrative is fair on women or not; I dare say, quietly, that it is not necessarily unfair.

Machaut was a man too, possibly as horribly prejudiced as everyone else, but through his music and poetry he aimed to go beyond the visible barriers, and to do the inevitable: worship beauty in the form of a woman. Who could really blame him for that.

Maybe John of Patmos’ struggle (a man versed in Greek, possibly familiar with the classics, an man who could have read Aristophanes, a jew, and perhaps a heretic jew at that – there are some), was that of a believer on the brink of disbelief: the Book of Revelation needed him, broke him, and made him mad in laughter and insanity. The split had taken place, God oversees a sea of metallic jade, the elders are just that, old and far removed, the Lamb is unreachable, repeatedly, and the whole thing does not seem to be addressed to humanity as such, since there is nothing we can do, other than hope that our given names are written in the book (Rev. 21.27).

The Book of Revelation shows, a touch unwittingly I guess, the inability of man to be good; or, as Northrop Frye put it, the perversion of his will: “confronted with a paradisaical situation”, he wrote, “man can only act the role of the serpent and destroy what is there.” Paradoxically a perverted will is a non-will once the automatism has set in and mechanical evil takes over, as it does, periodically, at all levels of human experience. The highest rewards promised and illustrated in the book are all too real and represent a higher degree of consciousness but the price paid is a brutal response from our animal nature in which, according to the in his own image formula of Gen. 1:27, is plainly also shared by the divine itself.

Frye was the first one to draw my attention to the structure of the Book of Revelation: it had to be somebody, and it was Frye. I had read quite a bit of his work, including The Great Code, which should have put me on the trail; only there was no trail to follow then. I reread that book, together with Anatomy of Criticism at least another two times. Like Harold Bloom intimated in the introduction to the latter, Frye has influenced me in ways that I am possibly not aware of. His “anatomy” of the Book of Revelation sits at the very beginning of my drafts book, and I have turned to it for structural purposes in numerous occasions, and of which hopefully I will have much more to say on another occasion.

Returning to John of Patmos, it is not impossible that he was the first to see Jesus as the model antihero, repeatedly a lamb in the book, or simply that he could not stomach his Nietzschean all-too human shape or form. In Revelation 12, quite unexpectedly, the hero model turns out to just been born, and this is something that, possibly more than anything else in the repetitive accounts of the Book of Revelation, tears the narrative into tatters and rags.

This fact, in my view, accounts for much of the impersonal and petrified glimpses that John has of the deity. I mean, John was obviously overwhelmed by a vision of a wrathful deity that went beyond the usual extermination procedure of the Old Testament, regularly inflicted on the deserving lot (Isaiah 24 is my favorite example: “the earth also is defiled under the inhabitants thereof”). Giant windmills wave their frightening sails repelling the charge of John’s sound judgment, lift him up in the air and spew him out all the way down from immeasurable heights. The vision of the dragon and the beast are, probably, the most terrifying personifications of the wrath of I am aware of: nothing comes close, in fact, no Behemoth no Leviathan. The commingling of ultimate evil in man’s nature is the inevitable result, one may say, of the intimations of man’s own soul (now so “near the fire”) with the divine, which throws humanity with one titanic kick in the back into modernity itself: the genii is out of the bottle and what the fate of the New Testament and its supporters shows us is that humanity’s visionary advance is an irreversible process and a terrible one too.

Only one thing can somehow mend the irreparable breach in the image of the divinity, now split asunder by an emerald sea: the healing power of the feminine. Who knows, in a long string of interpretations and “multifaceted” interpretations this one could fit just as well. Another matter is whether John was aware of it or not, and hence his haste, and the embarrassing silence thereafter.

Recalling now the title of this entry it is clear that the musical content of the oratorio, in its detail, may be revelatory in that it informs the attentive listener about what the author considers the central message of the Book of Revelation: the “evitable” fall of man in apocalyptic (revelatory) contrast with the inevitable one, when our first father (or was it a surrogate..?) was kicked out of paradise by a jealous, carnivore God (our real father..?) who, let us use a certain measure of poetic license, may have taken the shape of a serpent to seduce Adam’s lawful wife (or repossess his lover, for that matter). It certainly would explain a lot and by no means would I consider Yahweh (or Elohim) to be less of a trickster than Zeus or Hermes.

These speculations fit with the character of the Bible as a whole from the perspective, mine, musical, of the Book of Revelation: a major deception, or double-cross in a more modern fashion, of the human effort by a powerfully demonic god. A god that, together with the whole of so called physical reality such as the sun, the sea, and the stars, is cast out right at the end of the Apocalypsis as another fabrication of our limited senses and our limited courage. And this may explain too why the God of Rev. 4 and that of Rev. 22 differ so much, one as unmovable, the other as pure light, having cast out (like the first heaven, the first earth, and the sea) his own evil shadow. Perhaps not. But it can be read that way.