If, by some twist of fate, only the first eleven chapters of the Book of Revelation had been preserved, the doctrines and dogmas of Christianity would still regard this text as a work of profound religious and spiritual significance. Yet it is in the full span of its twenty-two chapters that the true complexity and depth of John’s apocalyptic vision unfold—a vision that has compelled me, almost against my own will, to embark on the daunting task of translating it into music.

See below, The “Two” Revelations

If writing music to the Book of Revelation would simply require to “paint” all those images with musical colors, while rigging them with an effective harmonic edifice I may have already abandoned this project years ago. Why I finally resolved to undertake this monumental project remains, to some extent, a mystery even to myself. It was not merely a matter of setting vivid images to harmonious tones or constructing an imposing harmonic edifice upon which to hang these prophetic scenes. Rather, it was an imperative—a calling that seemed to insist upon itself, demanding expression without recourse to shortcuts or musical artifices, and transcending considerations of tonal or atonal modalities.

Introduction: John and The Book of Revelation

For a brief summary of my musical approach to the Book of Revelation I refer the reader to the page dedicated to the Apocalypsis Iesu oratorio.

We can only speculate about the circumstances under which John of Patmos penned the Book of Revelation. Was he a young man, his imagination ignited by tales of the world’s end? Did the inspiration strike during an unjust imprisonment, akin to Cervantes, amidst the stark brutality wielded by those in power—the ones who make the laws and hold the keys to enslavement? Perhaps he was an elder, overwhelmed by visions that besieged him relentlessly, feverishly inscribing what he could scarcely comprehend himself. Did these revelations descend upon him in a singular, blinding moment, or were they the culmination of a lifetime’s travail—a final, encompassing vision of an ancient world teetering on the brink?

While we possess approximate dates—whether around 68 AD, before the Temple’s destruction, or circa 96 AD—and scant details of his biography, much about John remains shrouded. Some scholars posit that he did not complete the Book of Revelation himself, that perhaps a disciple, lacking the master’s finesse, assembled and ordered the material into the form we now know. I think of great composers in Hollywood who have assistants, or of Asimov’s workshop populated by diligent helpers. As a composer grappling with this text, such considerations bear practical significance. The author, be he singular or composite, exhibits an artistic instinct that invites deeper exploration—even after all these years. For me, as for most, he is John of Patmos, and his story fascinates me.

The problem of structure in the Book of Revelation

For a more itemized look at the structure of the Book of Revelation I refer the reader to the article in Wikipedia.

Narrative Structure

The chain of events presented to us in the Book of Revelation could be summarized as follows (according to the RSV outline of Revelation):

- Rev 1:1 Introduction and Salutation

- Rev 1:9 A Vision of Christ

- Rev 2 – 3 Message to the 7 Churches

- Rev 4:1 The Heavenly Worship

- Rev 5:1 The Scroll and the Lamb

- Rev 6:1 The Seven Seals

- Rev 7:1 The 144.000 of Israel Sealed

- Rev 7:9 The Multitude from Every Nation

- Rev 8:1 The Seventh Seal and the Golden Censer

- Rev 8:6 The Seven Trumpets

- Rev 10:1 The Angel with the Little Scroll

- Rev 11:1 The Two Witnesses

- Rev 11:15 The Seventh Trumpet

- Rev 12: 1 The Woman and the Dragon

- Rev 12:7 Michael Defeats the Dragon

- Rev 12:13 The Dragon Eights Again om Earth

- Rev 12:18 The First Beast

- Rev 13:11 The Second Beast

- Rev 14:1 The Lamb and the 144.000

- Rev 14:6 The Messages of the Three Angels

- Rev 14:14 Reaping the Earth’s Harvest

- Rev 15:1 The Angels with the Seven Last Plagues

- Rev 16:1 The Bowls of God’s Wrath

- Rev 17:1 The Great Whore and the Beast

- Rev 18:1 The Fall of Babylon

- Rev 19:1 The Rejoicing in Heaven

- Rev 19:11 The Rider on the White Horse

- Rev 19:17 The Beast and its Armies Defeated

- Rev 20:1 The Thousand Years (Millennium)

- Rev 20:7 Satan’s Doom

- Rev 20:11 The Dead Are Judged

- Rev 21:1 The New Heaven and the New Earth

- Rev 21:9 Vision of the New Jerusalem

- Rev 22:1 The River of Life

- Rev 22:8 Epilogue and Benediction

The problem of a list of facts and figures is that the book of John does not follow an easily intelligible timeline, indeed, its very recurrent and obvious sequences of seven do not help at all, to the point that some authors, with some justification, consider it as a distraction.

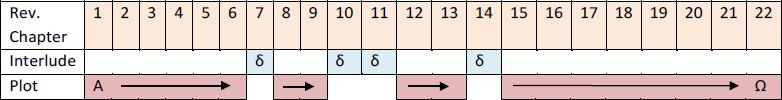

The chain of events within the Book of Revelation resists simple linearity. Its recurrent sequences of sevens—the seals, the trumpets, the bowls—do not readily yield a straightforward timeline. Indeed, some interpreters regard entire chapters as digressions or interludes, extraneous to a supposed central plot. They see this plot as (at least roughly) linear and consistent with a main sequence of events. These digressions are often referred to as interludes. I disagree with this interpretation. The text seems less a linear narrative and more a tapestry woven with threads that cross and recross, forming patterns both intricate and profound.

Α → Ω

Let us consider the notion of a linear progression from an initial point, Alpha (Α), to a terminal point, Omega (Ω):

In this framework, the so-called interludes—chapters 7, 10, parts of 11, and generally also 14—are viewed as deviations from the main narrative arc. Yet I find this perspective limiting. While such digressions are plausible, even in the biblical context (like the Cervantine kind in *Don Quixote*), we should delve deeper and ask whether another configuration more responsive to the narrative exists. The text seems to radiate from different centers, sometimes getting nowhere; it is, in a word, an antiplot.

Septenaries and other key elements in the Book of Revelation

The septenaries in the Book of Revelation, it should be said, would allow me to reuse the same material, varying it or re-elaborating it depending on the circumstances. This already constitutes in itself a great help, and it allows me to find some orientation as to the planning of the project. The task in this case would be to identify the septenaries and conceive the work as a series of musical variations or elaborations of a subject or group of subjects. And musically this is feasible: narratively speaking (though perhaps I should say “narratologically”, as pertaining to

narratology*

) I do not see it. Or simply I did not see it viable as a musical form that could sustain the whole, or at least to give the work a coherence that was beyond that of the musical form itself, one that needed to embrace the meandering meaning of the text.

Worse still: if the correspondence between all septenaries was used as a musical artifice, this would imply that some images or objects would become charged with an excessive importance, or sometimes devalued, or associated with conflicting or undesirable content in a different septenary (a content that may not be relevant at all just then). There are ample references in the text that make significant association of certain elements (objects, characters, etc.) to others who are not included accordingly in another septenary.

Some of these elements, such as the Book or the Two Witnesses, that seemed crucial to me to understand the message of the Book of Revelation, were not reflected satisfactorily in any of the numerological series that I could identify. I can certainly see a human-to-demonic association of the Two Witnesses (the two olive trees, two candelabra) with the two beasts, and the book with Satan’s deceitful propaganda unleashed in Rev. 13:14, and 20:7-10, that had afflicted and corrupted Babylon.

But for these opposites to make it into the overall musical structure I would have to (like I did) drop the septenaries as the main pillar sustaining the musical edifice. The septenaries are still musically there, to be sure, but the music has moved to enhance and connect more important correspondences and themes: those that connect John of Patmos’s priorities and mine as a reader or listener.

If to all this we add the fact that there are other important “numbers” in the Book of Revelation, specially twelve and four (five and six are also there, but to a lesser extent), these numeric symbols threatened with having to rethink the musical structure in numerological terms, and this did not convince me at all; despite knowing that elements of numerology and astrology had to be present in the mind of John of Patmos. To the point in which whole chapters of the Book of Revelation seem to be written large in the late summer night sky.

Septenary structure

For further references and outline see this.

There are numerous erudite views of how to divide the Book of Revelation in series of seven events. The most obvious series leave no doubt and are included by many, but there are others that have been proposed over the years.

For a more thorough treatment of the subject I refer the reader to Biblical and Classical Myths, by Northrop

Frye*

and Jay MacPherson.

The Book and The Little Book

(Rev 10:9 KJV)

Take it, and eat it up; and it shall make thy belly bitter, but it shall be in thy mouth sweet as honey.

The appearance of the “book” (βιβλίον, *biblion*) in Revelation 5, and its counterpart, the “little book” (βιβλαρίδιον, *bibliaridion*) in Revelation 10, emerged as significant thematic motifs. The directive to John to consume the little book—sweet in his mouth but bitter in his stomach (Rev. 10:9)—symbolizes the arduous task of internalizing and proclaiming profound truths. This motif compelled me to reassess the musical structure, allowing this theme to weave coherently through the composition. Additionally, the associations of the book thematic with what John had to announce to the “peoples, languages, tribes, nations, peoples, and kingdoms” (we missed one for an interesting sevenfold, maybe faithful?) were too obvious. Here, I thought, is the key to the book, simply that it is a book: not a treatise, not a code, nor anything else. And to John, writing that book must have cost him dearly, to the point of tormenting him even.

“Go, take the book which is open in the hand of the Angel, who is of standing on the sea and on the earth.”

Revelation 10:8

To start writing this music I needed something stronger than the numbers, and this was what I found: a story about a character tormented by visions that he saw around him as much within himself.

He wrote a book (Revelation) that sits as much within, as atop of another book (the Bible) which he references constantly in the text. Certainly he had no idea that one day his book (or little book perhaps) would end up as the final chapter of the Bible, a book he knew so well, promoted, read, and worshiped by peoples he could not quite identify himself with (the Pauline Christians), or even agree with, and with the bitterest of ironies, destined to be in charge of the “Babylon” (Rome) he hated so much.

Not much given to letters, perhaps, but clearly struggling to articulate his vision, or visions, in an intelligible whole; John was an author who, since nearly two millennia, also had to come to terms with structural problems. Perhaps John had (more than once) to redo his work, to borrow from one side to put in another, rewrite and erase, rip paper or burn scrolls. Sometimes it might seem that all that imaginative tidal wave came all at once, almost obliterating him. But I doubt it. I think there are enough signs that the “book” took him pains to write and to a certain extent edit too. In my view there are too many reworkings for all that to have happened at once, and perhaps that is where some of those septenaries

The jump from the first to the second part, with the birth of the Messiah is sometimes understood as a strategy to increase the intensity of the Book of Revelation: “the bad guy enters” so to say. But I do not see it. Those visions came in a “before” or “after” a first draft: they are simply too powerful. Maybe so powerful that John left only a sketchy trace of those, the most chilling shocking images.

John seemed at times obsessed with his hatred of Rome, Egypt and Babylon of the book. Perhaps he was a man involved and active in the politics of his time.

Maybe (they are already many maybes), what today seems most spectacular about the Book of Revelation is what took John more efforts to articulate: those spectacular visions of monsters and disasters, evil megalopolis and paradisiac heavenly cities that altered the balance of his writing and of which he left us (with the exception of Rome-Babylon and the New Jerusalem) only an outline. Who knows, maybe even the Book of Revelation was originally an epistle that went out of hand, because John was not destined to teach but to reveal.

The “two” Revelations

Compositional premises

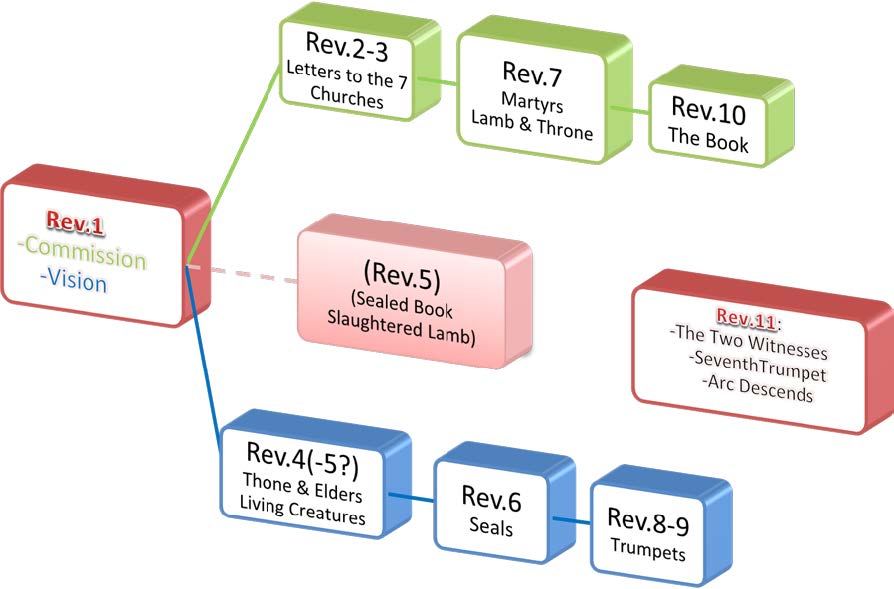

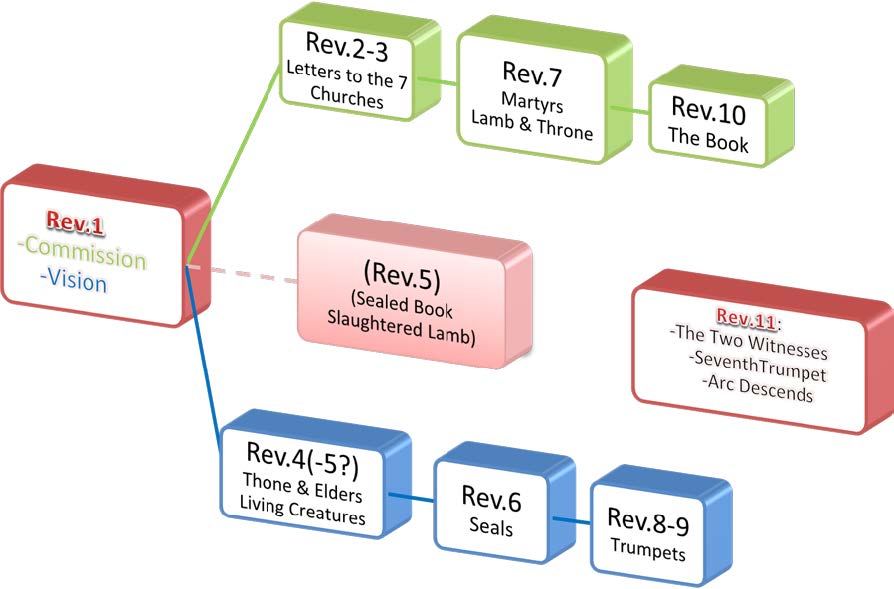

Through repeated readings, I began to discerned a kind of double-helix structure within the Book of Revelation—an intertwining division that aligns with both thematic content and emotional intensity. The text, in my view, seemed to naturally separate into two arcs, which I have come to call the Missionary Cycle and the Visionary Cycle. These terms encapsulate the dual facets of John’s work: his role as a messenger to the churches and as a seer of profound cosmic visions. John’s narrative is simultaneously embracing these two missions, as if the eleven first chapters were occurring simultaneously with the subsequent eleven chapters from Rev. 12 to Rev. 22.

The “First” Revelation Arch

The first eleven chapters cover the ground running from:

- Vision/Mission

- Call to the apostle, his mission (Rev. 1-3) and vision (Rev. 4-5)

- Call to the apostle, his mission (Rev. 1-3) and vision (Rev. 4-5)

- Evil/Suffering, Destruction/Judgement

- Destruction of wicked Earth (riders and trumpets, Rev. 6, Rev. 8-9)

- Suffering of the faithful (Rev. 7, and also Rev. 11)

- Temporary victory of evil (Rev. 11:7-10, along with the appearance of the beast arising from the abyss)

- Arrival of the kingdom and the final judgment (Rev. 11:15-18)

- Fulfillment

- Final revelation of the ark of the covenant in the sanctuary of God in heaven (Rev. 11:19)

In Rev. 10:7 we are told that:

[…] in the days when it was the voice of the last angel hear, when put to sound, it will have accomplished the mystery of God.

That is exactly what happens in 11:15. Why does Book of the Revelation continue with eleven additional chapters after that? We may have already answered that. Could it be that the persecution and banishment that John (an elder) suffered pushed him to adopt a more anti-establishment stance on (if I am correct) his first half of Revelation? Could it be that he felt compelled to revisit, or recreate his vision without disavowing his first more admonishing approach? Could it be that he wrote two versions of Revelation, and his disciple or scribe could not (or dared not) choose for whatever reason or circumstance?

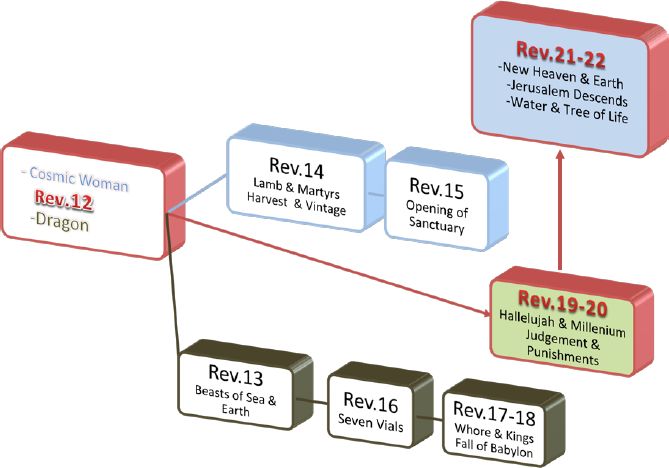

The “Second” Revelation Arch

There is no doubt that the second part (chapters 12 to 22) offers a similar structure, and possibly identical themes when compared to the first:

- Vision/Mission

- Vision of the Apostle (Rev. 12)

- Vision of the Apostle (Rev. 12)

- Evil/Suffering, Destruction/Judgement

- Destruction of wicked Earth by dragon (Rev. 12:13, together with beasts rising, Rev. 13) and by angels (Rev. 14 second half, and 15-16, vials)

- Suffering of the faithful (Rev. 14, first half)

- Temporary victory of evil (references in Rev. 17:17, 19:19, 20:9)

- Judgement of Babylon-Rome (Rev.18) and men (Rev. 19:2 and 19:11, Rev. 20:11 & ff.)

- Arrival of the kingdom (marriage of the Lamb, Rev. 19:7) and the final judgment (Rev. 19-20)

- Fulfillment

- Final revelation of the New Jerusalem (Rev. 21-22)

We may never get to know how the twenty-two chapters that make up the final draft of the Book of Revelation were written. There is no reason to think that the so – called grand visions came last. Perhaps the most arduous task was to give the whole work an epistolary and communicable form, i.e., to write the first eleven chapters after having experienced the dizzying roller coaster that goes from the appearance of the celestial woman until the arrival of the New Jerusalem. What good are these great visions in isolation? The ancient world was familiar with beasts, dragons, and celestial apparitions. John needs to provide his visions with a new Christian context but something seems to be blocking the way: this may be the reason why there is a continuity after chapter 11: the image of God portrayed in the first part is simply unreachable. All that will change in the final apotheosis in chapters 21 and 22: an apotheosis of feeling and true Christian faith.

I am not attempting to resolve issues that have been debated for almost two thousand years, and without being fully solved for all involved. I just want to point out where my experience in reading the Book of Revelation led me, while trying to shape a coherent musical outline of that work. John of Patmos, it appeared to me, seemed to have written two books in one. There was no need to destroy the earth so many times with all sorts of plagues and disasters: it always felt like John was reaching for something he could not quite shape completely (until the very end of the work), and at times the whole thing reads like a draft.

Maybe at some other time it would be convenient to illustrate the composition process (including stylistic and syntactic considerations) in more detail, but here I am only concerned with considerations about the structure of the Book of Revelation. A structure, again, that must be plausibly reflected in a musical form that does justice to the story, not the store on a Procrustean bed.

“Double Arch” as Compositional Plan

From a creative perspective, one that is committed to give meaningful expression to its subject, the Book of Revelation tells us most of the time that everything has a beginning and an end, an Alpha and Omega. It speaks to us, calls us in a sense, to represent it and say it one more time, to retell the story with different accents and rhythms if that is what it takes, without adding or subtracting to it; that of itself is perhaps the greatest challenge of all. The book itself is the beginning and end of a cycle, one that repeats itself indefinitely but which is every time accomplished in each of us, who are the key and the axis of a wheel that does not stop.

That’s what God, in the account of the Book of Revelation, tells John: “I am the Alpha and the Omega, the Beginning and the End,” a new expression, like the famous formula of Einstein for physics, embracing God with the simplest possible written expression: a to z, α and ω.

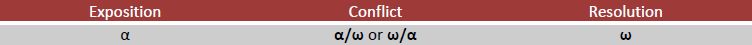

Apocalypsis Iesu: Formal Structure

The formal structure of the oratorio Apocalypsis Iesu is determined by the basic structure already mentioned (α-ω) underlying the Book of Revelation in different ways. This way what the musical exposition of the book refers is clearly an arc:

Simple structure of Book of Revelation

Apocalypsis Iesu – Juscheld

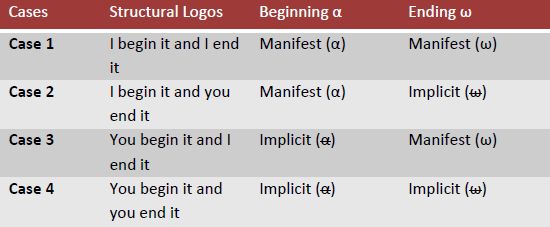

Or as we say sometimes in other contexts “thesis – antithesis – synthesis”. This meta-structure could be seen as a formal universal resource present ubiquitously in the cultural and creative production of our human community through time: a literary structure, as we now say, or mythological, as we used to. From complex matters such as the Odyssey or the saga of Heracles in Greek mythology to a simple grammatical sentence (“Heracles is a Greek hero”), all creation or human utterance has a beginning and an end, either implicit or fully stated. This order is what primarily gives meaning and guidance to that process of rapport between the author and the reader. In other words, and from the point of view of the hypothetical author and potential reader (I being the author, and You he reader or audience):

Structure Reader-Narrator in the Book of Revelation

Apocalypsis Iesu – Juscheld

In this context the work of John has God himself as a “structuring” subject, that is to say, the A and Ω, the cycle itself. Depending on the perspective we take we could situate ourselves in the first case, which we may call “epistolary”, or in the latter case which we could then call “visionary”. The latter is characterized by the absence of direct speech or even description of any kind: it is the symbol itself before our eyes, or in our minds.

In other words, in the Book of Revelation the characteristic arc shape of all creative production is complicated by the fact that John is sometimes an active agent (Case 1), included in the center of the narrative, and other times he is a mere transmitter of visions that present themselves with increasing intensity and significance (Case 4). The reader, luckily, has to settle for Cases 2 and 3, and therein lies the conflict, since it seems highly improbable that most readers can share the visionary experienced that overwhelemed John in the island of Patmos, let alone share the insights of the Alpha and Omega itself.

Musically speaking this results in a different emphasis (theme, orchestral, harmonic, etc.) depending on the plane (or Case) we are moving on: the epistolary or the visionary.

Cycles

The musical structure of Apocalypsis Iesu is that of two parts (Part I and Part II) that share two common thematic areas, as I have already proposed: those thematic areas could be called, as far as their reader is concerned, humanistic (corresponding to what epistolary and missionary that is included in the book), and spiritual (or visionary). The first, or humanistic, deals with what Juan is doing (seeing, listening, and writing) and has experienced (his possibly traumatic biography). The spiritual perspective is the one that John transmits to us as a witness, the one that he attempts to articulate with the apocalyptic imagery that constitutes the most spectacular side of the Book of Revelation.

What necessarily interests me as a composer, in addition to the theme, is the degree of emotional intensity with which Juan involves the reader, not only with each of his images (or symbols), but also their hierarchy.

Thematically these two areas, the humanistic and the spiritual, are intertwined in two musical arcs, both with a clear and spectacular beginning, a series of conflicts/trials, and a typically apocalyptic or revealing resolution:

- Part I (first apocalypse):

- Heavenly Vision and Commission

- Contrasts between suffering of the faithful and destruction of the wicked

- Opening of the Sanctuary of God and vision of the Ark of the Covenant

- Part II (second apocalypse):

- Cosmic Vision

- Sharp contrasts (punishments and rewards)

- The New Jerusalem descends (without sanctuary)

Each part establishes a hierarchy of images or symbols that can be understood as framed in a self-sufficient (or in some way creative) musical structure. Let’s call those parts “acts” if you like, and those thematic areas that are intertwined in these missionary and visionary . In order to define these acts more precisely, or to give them a more relevant meaning in the context of the book, I am going to call the predominant orientation cycles in each one of them. Thus, Part I will correspond to the Missionary Cycle , and Part II to the Visionary Cycle , without losing sight of the fact that both are inextricably linked in the narrative of the Book of Revelation.

Part I: Missionary Cycle

The first part of Apocalypsis Iesu goes from App.1 to App.11. These two chapters constitute a diptych in the form of a choral symphony.

Part II: Visionary Cycle

The second part of the oratory is structured around a theme of antagonisms significantly more marked than in the first part. There is a clear continuity between Rev. 12-13, Rev. 14 brings back the missionary (or epistolary, elevated to revealing) facet of the Book of Revelation (and, in a sense, Rev. 15 might be understood as a continuation, despite to introduce the seven angels of plagues). Other thematic pairs are Rev. 17-18, 19-20, and 21-22.

Final Considerations

To understand the Book of Revelation from an artistic perspective we have put ourselves first in its author’s place. That is the first and insurmountable problem: Where to start? So much has been written (and more is being written) about the Book of Revelation, that it is simply impossible to start anywhere other than reading it. Herein lies the second problem: we may not possess the parameters or even the same categories of judgment (or thought in general) as those early disciples of Jesus, in the era that followed the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem.

What to do? The answer: read it, in any case, and reread it until its structure, the one that best satisfies the questions with which we approach the book, makes its way into our minds. An additional, or perhaps complementary option is to spend a lot of time reading apocalyptic literature, and the comments that two millennia of Christianity have produced about the book of Juan de Patmos. Over time this corpus of comments, which is going from praise to denigration, it begins to take more or less, and figuratively, the shape of a cross: the spiritual (or “pneumatic”) axis goes from what we could call theological, going down to the purely historiographic terrain; both use the symbol as an interpretive tool, either in their mysterium aspect, or as a code to some extent decipherable. The other axis, let’s call it humanistic, inevitably horizontal, goes from religious fanaticism to its other extreme, the complete disqualification of the book; here fits both the speech and the most abject intolerance. In the midst of all this, how could it be otherwise, is the figure and the message of Jesus, of Christ.

As far as the creative task inspired by John’s work is concerned, the option of trying to embrace the message of the Book of Revelation through an artistic work remains valid, as much now as it has been since its inclusion in the canon. Many artists have dedicated their creative genius or at least their continued effort to this subject (see here or here for a good review of these efforts). Whenever the artist has found his inspiration in the Book of Revelation, he has to ask himself a question that could be called structural: the unity of the work. The vision must encompass the meaning of what the apocalyptic landscape present in the text shows, that outlandish parade of images to which only the apocalyptic adjective does it justice. And this is already a third problem: how much can the visionary and detailed gaze of the person who has to create it cover? It could be said in another way: what legitimates you to do it? Why do you want to do it?